‘Olga de Amaral’ at Lisson Gallery Los Angeles: Gold, Fiber, Light, Palladium, and the Ethics of Patience

Olga de Amaral Casa Amaral, Bogotá, Colombie, 2013 Photo © Diego Amaral

‘Olga de Amaral’ at Lisson Gallery Los Angeles arrives with a composed gravity. Spanning works from the early 1970s through 2018, the presentation traces the artist’s six-decade investigation into fiber, light, and transformation: an inquiry that has long exceeded the boundaries of weaving, even as it remains rooted in its discipline. Rather than asking the viewer to consume images quickly, the exhibition invites a gradual interpretation, an attunement to material and light, and to patience as an ethical proposition: not simply a condition of viewing, but a labor of perception.

Exhibition view of ‘Olga de Amaral’at Lisson, Gallery Los Angeles, 14 November 2025–January2026 © Olga de Amaral, Courtesy Lisson Gallery

“From my earliest days to my most recent pieces, I have always been inhabited by color, yet I am still looking for its mysterious soul.”

— Olga de Amaral

My relationship to de Amaral’s work predates this institutional context. I first encountered her work as a teenager at the Museo de Arte Moderno de Medellín while visiting family in Colombia. At the time, my art historical knowledge was still forming, shaped largely by repeated encounters with Fernando Botero’s work in Bogotá and Medellín, where I spent hours studying his paintings and sculptures. Those trips were also marked by time spent playing piano at the Biblioteca Luis Ángel Arango in Downtown Bogotá, where music, architecture, and visual culture quietly intertwined. Encountering de Amaral then introduced a different register altogether, one rooted not in figuration or monumentality, but in material intelligence, restraint, and the visceral possibilities of structure.

Those early visits were further shaped by time spent at the Museo del Oro in Bogotá, where pre-Columbian works articulate a relationship to metal not as currency or display, but as ritual, offering, and spiritual conduit. My family is from a small town called Gámeza in the Andean mountains of Boyacá, a region historically linked to Muisca culture and the mythology of El Dorado. Within this longer historical frame, Colombia emerges not simply as a contemporary nation-state but as an ancient landscape in which gold and other metals carried cosmological meaning, an understanding that quietly underpins de Amaral use of precious materials as vessels of memory, devotion, and spirit rather than economic value.

‘Olga de Amaral’ at the Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain, Paris (2024) © MARC DOMAGE

That early encounter gained new resonance years later when I encountered de Amaral’s expansive retrospective, ‘Olga de Amaral’, at the Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain, Paris (2024). I had first visited the Fondation Cartier in 2017 as a student living in Paris while studying medieval art history. Returning to the institution through de Amaral’s exhibition activated those earlier frameworks, as the works transformed the space into something closer to an altar than a gallery, an environment devoted to material, light, and worldly reverence. The exhibition unfolded within a darkened, architecturally responsive setting where light shifted gradually, enveloping the viewer in an almost devotional atmosphere. The experience was overwhelming in scale and ambition, presenting a near-total immersion into Amaral’s cosmological vision.

One work in particular, Bruma R (2014), crystallized this effect. Within a room filled with works from Amaral’s Bruma series, the installation created a fog-like field of suspended material and light that felt immersive rather than observational. That experience immediately recalled Anthony McCall: Solid Light at Tate Modern, London, in which projected light becomes a sculptural volume activated by the viewer’s movement. In both cases, form is not fixed but altered through presence, duration, and perception.

‘Olga de Amaral’ at the Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain, Paris (2024) © MARC DOMAGE

This mode of world-building through light and structure also brought to mind Tony Cragg’s exhibition Sculpture at Dirimart Dolapdere, Istanbul, as well as his presentations at Marian Goodman Gallery in New York and Los Angeles. Cragg, like de Amaral, belongs to a generation of artists for whom sculpture operates as infrastructure—an organizing system through which viewers move, rather than an isolated object encountered frontally. Seen in sequence, these experiences reframed my encounter with de Amaral’s work in Los Angeles, positioning her alongside Cragg as an artist actively rethinking sculpture as a spatial and perceptual framework, while McCall’s work foregrounds how light itself can function as material that reshapes form in real time.

At Lisson, the register shifts. The white-walled clarity of the space introduces moments of apprehension, not because the works lack force, but because their restraint demands a different mode of looking. The generous spacing between objects allows each work to be apprehended holistically, materially, structurally, and temporally, yet the installation also prompts a desire for greater dialogue among the works themselves. Rather than forming a fully immersive environment, the exhibition unfolds as a sequence of discrete encounters. The objects seem to call toward one another, asking to be read relationally rather than in isolation.

Olga de Amaral, Eslabón Familiar,1977, Hand-spun horsehair and wool238.8 x 73.7 cm94 x 29 in© Olga de Amaral, Courtesy Lisson Gallery

Olga de Amaral, Nudo 19 (turquesa), 2014, Linen, gesso, and acrylic293.4 x 17.8 x 17.8 cm115 1/2 x 7 x 7 in© Olga de Amaral, Courtesy Lisson Gallery

Two suspended works, separated by nearly four decades, reveal how Amaral’s approach to form has shifted while remaining materially consistent. In Eslabón familiar (1973), horsehair is wound, looped, and repeatedly turned back on itself around a supporting structure, producing a dense choreography of movement. The complexity of the work lies in its accumulation: coils gather, tighten, and suspend themselves in space, registering the pressure of the hand that formed them. This logic recalls Ruth Asawa’s engagement with wire, which emerged in part from her study of looped wire forms used by Mexican artisans to make coiled baskets and chicken traps, structures built through repetition, tension, and touch rather than design in advance. In both cases, the coil functions as a disciplined, almost militant gesture: flexible yet insistent, suspended yet held in place, animated by the labor that produced it.

Seen this way, the work captures the artist’s hand at its most elemental. Like a photograph, it arrests motion without erasing it, preserving the trace of touch while fixing it in space. By contrast, Nudo 19 (turquesa) (2014) reduces this logic to a single, decisive act. A column of turquoise-dyed linen threads, stiffened with gesso, is gathered into one knot near its apex. What appears minimal at first glance is structurally charged: the entire work depends on that solitary point of compression. Suspended between the ceiling and the floor, the piece oscillates between gravity and suspension, suggesting both weight and release. In this later work, Amaral distills weaving to its essential function, binding, expanding a humble gesture into a form that feels simultaneously anchored and buoyant.

Olga de Amaral, Ombrío A, 2017, Linen, gesso, Japanese paper, acrylic, and palladium (172.7 x 71.1 x 2.5 cm68 x 28 x 1 in) © Olga de Amaral, Courtesy Lisson Gallery

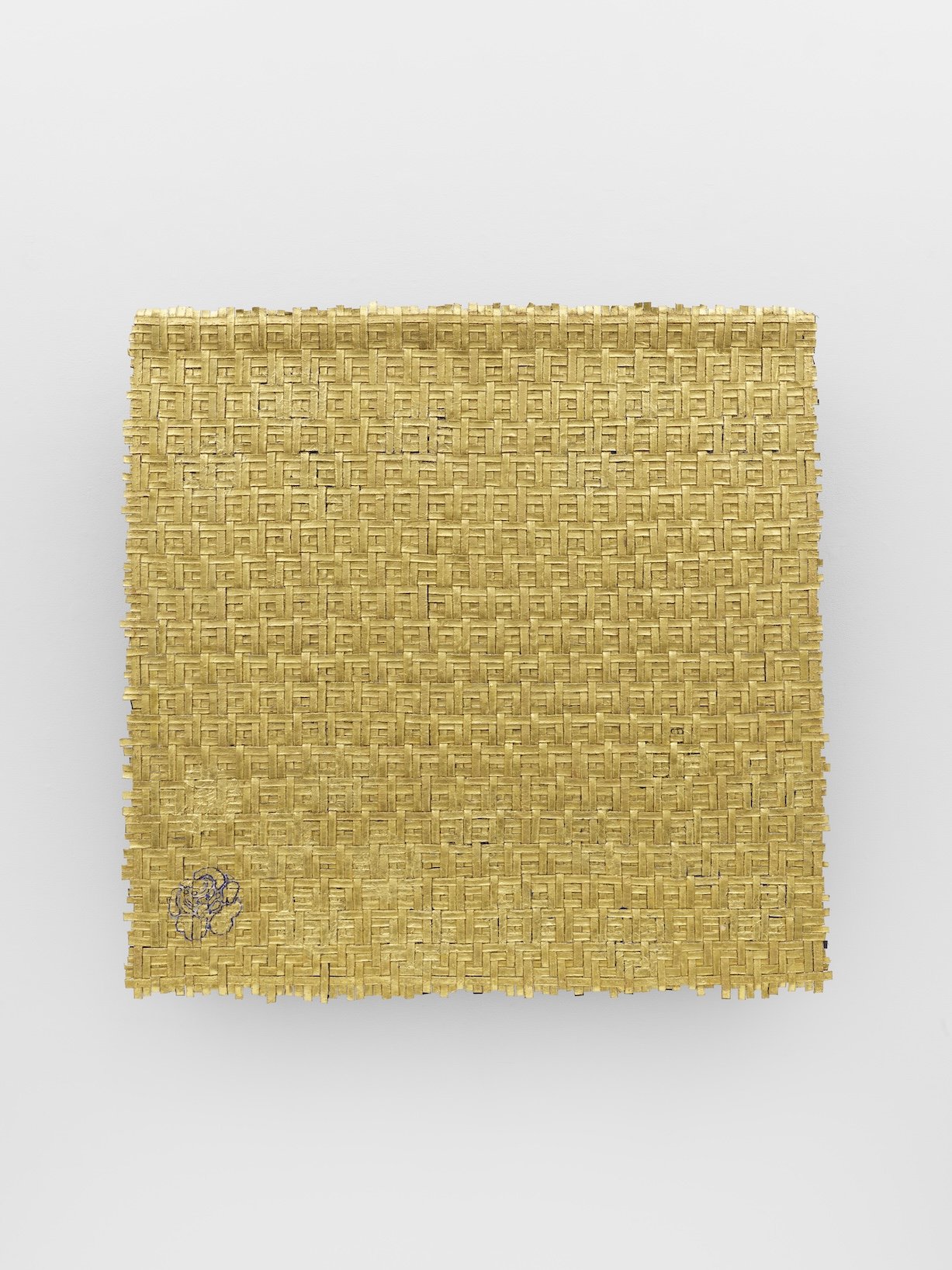

Olga de Amaral, Memento 9, 2016, Linen, gesso, acrylic, and gold leaf (133.4 x 132.4 x 1 cm52 1/2 x 52 1/8 x 3/8 in) © Olga de Amaral, Courtesy Lisson Gallery

A similar sensitivity to time and material emerges in Ombrío A (2017). Composed of linen, gesso, Japanese paper, acrylic, and palladium, the work reveals Amaral’s acute understanding of material behavior across decades. Gold leaf, when pure, resists oxidation; silver oxidizes and develops patina; palladium occupies a rare position, retaining the visual coolness of silver without tarnishing. Amaral’s use of palladium underscores a refusal to artificially seal or arrest material life. The surface retains its natural luminosity, rewarding prolonged looking and emphasizing time as an active collaborator. This understanding has been quietly formative in my own practice.

Another work that lingered after leaving the gallery was Memento 9 (2016). Constructed from tightly layered strips of linen arranged into a grid and overlaid with gold leaf, the work carries de Amaral’s signature geometry while opening onto architectural associations. The structure recalls Frank Lloyd Wright’s Ennis House textile-block system, suggesting a crossover between textiles and architecture. Over the gold surface, Amaral draws a delicate floral motif—an ephemeral inscription that reads less as ornament than as sigil, a gesture inscribed onto an earthen, golden body.

Across the exhibition, de Amaral’s grids, suspended forms, and layered surfaces resonate with broader lineages. The hanging structures recall Ruth Asawa’s wire sculptures, as seen in Ruth Asawa: A Retrospective at San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (2025) and The Museum of Modern Art, New York (2025-26), while the use of fiber and rope evokes Cecilia Vicuña’s precarious constructions and ritual bundles. These associations do not dilute Amaral’s authority; rather, they situate her within a continuum in which vessels, ropes, and armatures become carriers of meaning, history, and cosmology.

Her work also resonates in dialogue with Latin American modernists such as Eduardo Ramírez Villamizar; particularly 16 Torres / Torres del Silencio (1973), where repetition, verticality, and silence articulate space as a meditative structure; Fanny Sanín, particularly Acrylic No. 4 (1977), where chromatic restraint and geometric precision articulate painting as spatial rhythm; as well as Ana Mercedes Hoyos’s Ventanas series (1980s–1990s), in which light and material operate as thresholds rather than surfaces. de Amaral’s works do not depict landscapes; they become them.

Vue de la Casa Amaral, Bogotá, Colombia; View from Casa Amaral, Bogotá, Colombia; Olga de Amaral, Cenit, 2019© Olga de Amaral. Photo © Juan Daniel Ca

This expanded lineage also connects to Barbara Kruger's early textile works. In the late 1960s and early 1970s—prior to the text-based practice for which she later became widely known—Kruger produced large woven wall hangings from reclaimed materials such as ribbons, feathers, beads, and yarn. These works elevated materials associated with domestic labor and femininity into the space of serious art, asserting their intellectual and political weight. Rather than separating craft from critique, Kruger’s early textile practice fused them, establishing a material logic that would later expand into a broader investigation of value, power, and circulation—an evolution that runs parallel to de Amaral’s sustained commitment to material as both structure and critique.

More recently, this logic of material devotion as critique surfaced in Igshaan Adams’s exhibition I’ve Been Here All Along, I’ve Been Waiting at The Hill Art Foundation, New York. Adams’s work demonstrates how beauty itself can function as an intervention, holding political and ethical weight without requiring dissection or didacticism. In this context, fiber and domestic materials become an evaluation of waste, erasure, and hierarchy, asking what is allowed to matter and what is dismissed: the domestic body, the femme body, the racialized body, and the labor of bodies historically rendered invisible.

Exhibition view, "Olga de Amaral" at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Miami, presented with the Fondation Cartier pour l'art contemporain, May 1 - October 12, 2025. © Olga de Amaral. Photo: © 2025 Kris Tamburello.

In Los Angeles, the exhibition feels both comforting and overdue. Amaral’s work resonates geographically and culturally, yet its significance now extends far beyond fiber-based practices. Following major institutional presentations such as ‘Woven Histories: Textiles and Modern Abstraction’ at Los Angeles County Museum of Art (2023–24), which traveled to the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. (2024), and her retrospective ‘Olga de Amaral’ at the Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain, Paris (2024), later traveling to ICA Miami (2025), Amaral has firmly entered the realm of canonical art history. Her presentation in Los Angeles feels timely—not corrective, but confirmatory—situating the city and the Western US within a global conversation already underway.

What ultimately emerges from the exhibition is a meditation on patience: de Amaral’s methodical, finite approach to material challenges younger generations to reconsider intuition not as spontaneity, but as something earned through sustained engagement with matter. Fiber is not merely a resource in her work; it is a guide.

The exhibition also invites reflection on recognition and time. Like Carmen Herrera and Fanny Sanín, Amaral received widespread international recognition later in life, raising enduring questions about how gender, geography, and labor shape art historical visibility. While conditions are shifting, the exhibition quietly asks whether global instability continues to influence who is seen, when, and under what conditions.

At Lisson Gallery Los Angeles, Olga de Amaral’s work does not overwhelm. It waits. It shimmers. It insists on devotion to the material, to the process, and to the slow unfolding of meaning.

‘Olga de Amaral’ at the Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain, Paris (2024) © MARC DOMAGE

Olga de Amaral is on view at Lisson Gallery Los Angeles through January 31, 2026