Michael Rikio Ming Hee Ho Debuts First NYC Solo Exhibition at Fragment Gallery Featuring Trompe-l’Oeil Shaped Canvases, Text-Based Conceptual Art, and Contemporary Hawaiian Identity

Installation view of In now that i look back it was all falling apart but the pieces were all there: Michael Rikio Ming Hee Ho at Fragment Gallery, New York. Courtesy of Fragment Gallery.

In now that i look back it was all falling apart but the pieces were all there, conceptual artist Michael Rikio Ming Hee Ho presents his first New York City exhibition at Fragment Gallery on West 14th Street in Lower Manhattan with a body of work that reads less as autobiography and more as infrastructure, a coordinated visual and linguistic system built from the unresolved tensions of belonging.

Rooted in the polyethnic, Creole culture of Hawai‘i, Ho approaches identity not as essence but as residue: inherited, partial, felt, and never fully claimed. Through shaped canvas panels that use trompe-l’oeil — a painting technique that creates the illusion of three-dimensional depth — archival fragments and handwritten text are layered into single, faceted surfaces that blur the boundary between painting and object. These spatially assertive forms project toward the viewer like bodies in conversation, their dyed raw-cotton surfaces accumulating phrases and images the way memory accumulates keepsakes.

Installation view of In now that i look back it was all falling apart but the pieces were all there: Michael Rikio Ming Hee Ho at Fragment Gallery, New York. Courtesy of Fragment Gallery.

In BUT THE PIECES WERE ALL THERE (2025), acrylic wraps seamlessly across a large, shaped panel, its beveled edges operating as more than structural support — they become an activated perimeter. A hanging lei, a can label, a roadside horizon, and a handwritten note hover within a constructed depth that feels intimate yet architectural. The illusion of collage bends convincingly around the panel’s corners, but up close, the raw cotton surface, crisp paint edges, and subtle shifts in sheen reveal the work’s material precision.

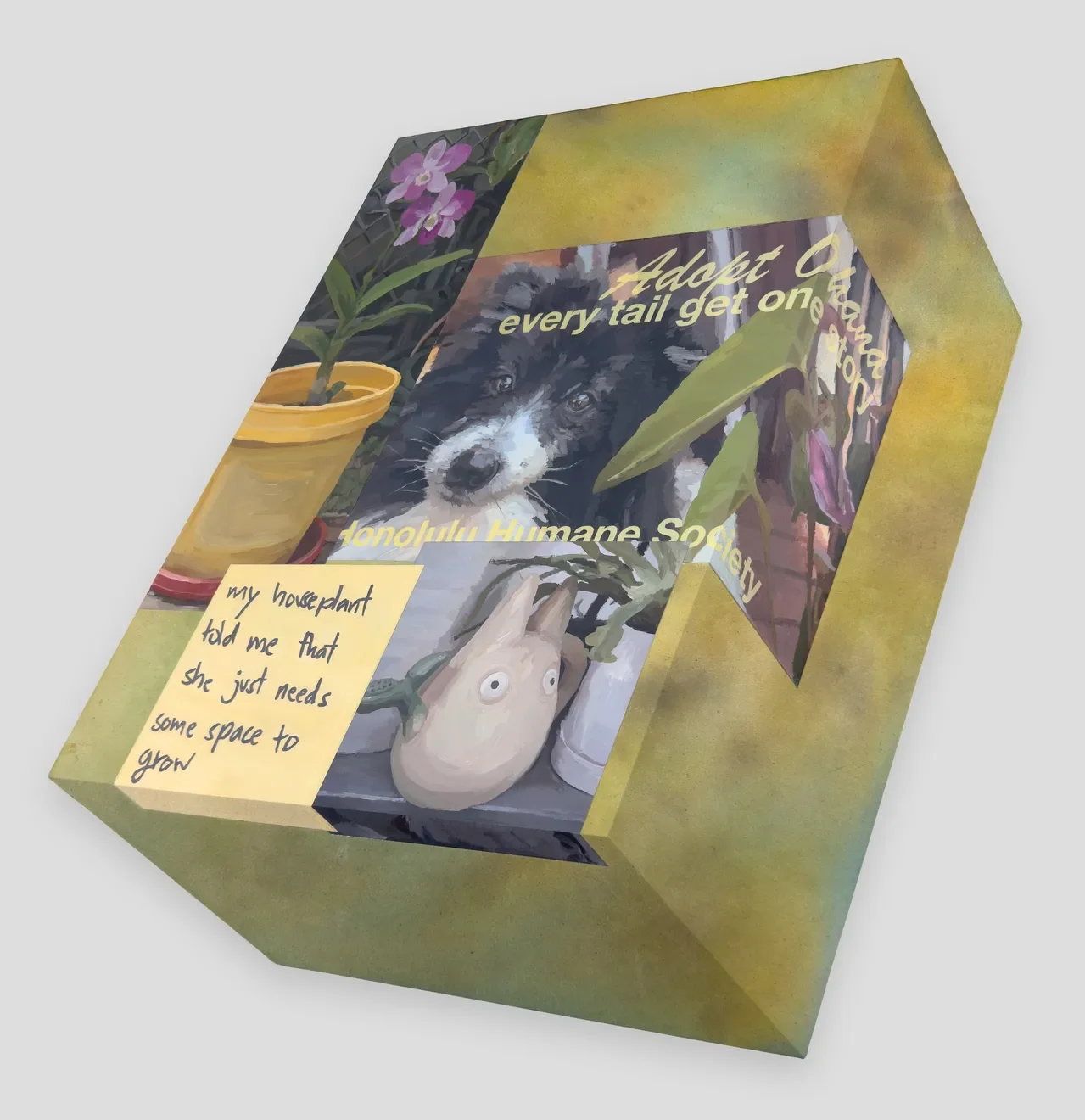

In CHILDLIKE AND COSMIC (2025), packaging, archival paniolo imagery, plants, and handwritten notes converge in a tightly layered composition. Images wrap across the edges, producing a quiet sense of movement as the work shifts between illusion and objecthood.

Throughout the exhibition, language functions as both declaration and doubt: phrases in Hawaiian Pidgin such as “certified local baddie… but certified endangered” present identity while simultaneously questioning it, revealing self-definition as performative, ironic, and deeply personal at once.

Michael and I met while studying at UCLA Arts in our introductory photography class in 2016, and we later exhibited together in Materiality and Language: Explorations in Form and Meaning, curated by Esthella Provas at Kotaro Nukaga, Tokyo (June 8 – July 31, 2024), where we are both currently. Since then, Ho has shown internationally, including at the Watarium Museum of Contemporary Art in Tokyo, and recently released his first collectible artist book, oh honey take all the damn time you need (Published by Sangeehut, 2026), a text-forward extension of his conceptual practice.

Installation view of In now that i look back it was all falling apart but the pieces were all there: Michael Rikio Ming Hee Ho at Fragment Gallery, New York. Courtesy of Fragment Gallery.

As he continues to rise among a new generation of artists working in text-based media, Ho distinguishes himself through the physicality of his geometric works, which resist the flatness of language while foregrounding it. Situated within a lineage that extends from postwar conceptual text practices to today’s post–social media linguistic field, his work proposes a new form of legibility: one that resists essentialized symbols while remaining disarmingly accessible. This New York debut marks not simply an arrival, but a sharpening of a moment in which memory, material, and language cohere into a practice unmistakably of this era, and distinctly his own.

In the following conversation, we discuss Ho’s formative years in Waimea on the Big Island of Hawai‘i, his early studies in linguistics at UCLA Arts, and how language became central to his practice. We talk about cultural ventriloquism, algorithmic identity, and the pressures of legibility in a post–social media era, as well as his studio life in Harajuku, Tokyo, where he bikes to work every day. Moving between memory, material process, and art historical lineage, Ho reflects on what it means to construct belonging through text, surface, and illusion, and why resisting easy categorization remains central to his work.

Michael Rikio Ming Hee Ho is building a custom-shaped canvas in his Tokyo studio in Harajuku. Courtesy the artist.

Michael Rikio Ming Hee Ho is painting with acrylic on canvas in his studio. Courtesy the artist.

Interview

AMADOUR:

Hi Michael, it’s nice to catch you at midnight while you’re working in Tokyo in the late afternoon. I’m so excited for this interview, also, And Now That I Look Back, It Was All Falling Apart, But the Pieces Were All There at Fragment Gallery in New York, which is phenomenal. Congrats! The work feels rooted in your love of family.

Can you describe your history working with text art? How did you arrive at focusing on language?

MICHAEL RIKIO MING HEE HO:

When I began studying art at UCLA Arts, I was also taking linguistics courses. As I studied post-war contemporary art and encountered conceptual text-based artists, that coincided with my fascination with semantics — how meaning is embedded in simple grammar and words.

Language felt deeply abstract to me. It made more sense than painting at first. I don’t think painting was as much of a calling as linguistics was.

When I think about the 1970s and 1980s, artists like Lawrence Weiner, Jenny Holzer, Barbara Kruger, and Christopher Wool approached language in a pre-social-media era. Our relationship to language is radically different now. I see myself continuing that lineage, but in a new linguistic condition.

AMADOUR:

Your paintings are very three-dimensional; they almost project off the wall. You also construct your own frames. Can you talk about dimensionality in your process?

MICHAEL RIKIO MING HEE HO:

Moving to Tokyo changed the way I think about space. In Los Angeles, I had the privilege of larger studio environments. In Japan, studio spaces are small and intimate.

So I began asking: if I have to make physically smaller works, how can they still assert themselves spatially?

The trompe-l’oeil surfaces and shaped canvases take up wall space. They tilt toward you. The words feel like they’re speaking. There’s a human posture to them. They occupy space like bodies.

All the shapes begin in 3D modeling software. I print templates, cut wooden panels, then edit imagery in Photoshop to bend around illusionistic surfaces. I use acrylic because it lets me build plastic layers without worrying about drying time.

There’s an oscillation between illusion and material rawness — between flatness and objecthood.

Michael Rikio Ming Hee Ho, SHE JUST NEEDS SPACE, 2025, Acrylic on cotton canvas panel, (49 W x 63 H cm | 19 W x 25 H in). Courtesy of Fragment Gallery.

Michael Rikio Ming Hee Ho, BUT THE PIECES WERE ALL THERE, 2025, Acrylic on dyed raw cotton canvas panel, (59 W x 49 H cm | 22 W x 19 H in). Courtesy of Fragment Gallery.

AMADOUR:

You write in Hawaiian Pidgin (Hawaiian Creole English), and your work exists within a polyethnic sphere. Can you describe growing up in Waimea, Hawaii, on the Big Island?

MICHAEL RIKIO MING HEE HO:

I didn’t think deeply about my multicultural upbringing until I moved to LA. There, identity felt binary. You belonged to a race, to an enclave.

In Hawaii, that binary doesn’t exist. I’m Japanese and Cantonese, but I never felt ownership over either identity. Local Hawaiian culture is inherently Creole — deeply entangled post-plantation history.

When I moved to Japan, a much more homogenous society, people expected to “see Hawaii” in my work. But what does that mean? Sunsets? Palm trees?

Local culture is far more complex than the tourist image.

AMADOUR:

You’ve mentioned cultural ventriloquism. Who is speaking in these works?

MICHAEL RIKIO MING HEE HO:

There’s always been a lack of ownership. I’m not Native Hawaiian. I didn’t grow up speaking Japanese or Cantonese. Even in Waimea, a paniolo cowboy town, I didn’t surf or hunt.

There’s a performative aspect in my work. A fantasy of what I wish I embodied. It comes from insecurity.

The longer I live away from Hawaii, especially in Asia, the more that insecurity intensifies.

AMADOUR:

Do you think your work speaks to a generational crisis of categorization in the age of algorithmic identity?

MICHAEL RIKIO MING HEE HO:

Yes. As monoculture disappeared, artists became comfortable fitting into identity categories. That pressure alienated me.

I wanted to fit into something digestible, but I knew it was inauthentic. Identity politics often feel formulaic — individuality must be consumable. That irony interests me.

AMADOUR:

Do you feel you’re trying to become legible or resist legibility?

MICHAEL RIKIO MING HEE HO:

I’m introducing a different kind of legibility.

In Hawaii, race politics aren’t binary. But for mainland audiences, identity often is. So I create entry points — like the paniolo cowboy. It’s a symbol people recognize.

I translate nuance without flattening it.

Michael Rikio Ming Hee Ho, I PROMISE YOU I’LL COME BACK, 2025, Acrylic on dyed raw cotton canvas panel, (84 W x 104 H cm | 33 W x 41 H in). Courtesy of Fragment Gallery.

Michael Rikio Ming Hee Ho, MY ISLAND GIRL, 2025, Acrylic on dyed raw cotton canvas panel, (34 W x 47 H cm | 13 W x 19 H in). Courtesy of Fragment Gallery.

AMADOUR:

I see your work in relation to Ronald Davis and Robert Rauschenberg through shaped surfaces, and perhaps even Njideka Akunyili Crosby in how memory and collage intersect. How do you see yourself in relation to art history?

MICHAEL RIKIO MING HEE HO:

That’s interesting. I definitely look at Ed Ruscha, Roni Horn, and Tsang Kin-Wah.

But I think we’re in a radically different linguistic era. Post-social media language operates differently.

I also love Sterling Ruby, Raymond Pettibon, and Tom Sachs. I actually own one of Tom Sachs’ NASA Chairs. There’s something about the objecthood and constructed authority in their work that resonates with me.

And Nora Turato, she’s capturing the cadence of language now in a way that feels ultra-contemporary.

I think I’m participating in something new within that lineage.

AMADOUR:

You’re working in Tokyo. Tell me about your routine.

MICHAEL RIKIO MING HEE HO:

My studio is in Harajuku, right in the center of Tokyo. Most artists here work in the countryside, but I need the energy of the city.

I bike to my studio every day. Cycling clears my mind. It gives me solitude before entering the chaos. Tokyo’s public transit is amazing, but biking feels freeing.

I spend time in neighborhoods like Shimokitazawa, where there are small cafes, bakeries, and jazz bars. That intimacy balances Harajuku’s intensity.

AMADOUR:

Tell me about your upcoming residency at Hart Haus in Hong Kong.

MICHAEL RIKIO MING HEE HO:

I’ll be there for a month and a half. I’m Cantonese but don’t speak the language. It feels like returning to something I lacked agency over.

I’ll make a new body of work and present it in a solo exhibition in May.

AMADOUR:

You’ve also been showing in Korea.

MICHAEL RIKIO MING HEE HO:

Yes, with Sangeehut Gallery. We released a book of poetry, oh honey take all the damn time you need, not a catalog, but pure text.

The gallery supports my conceptual focus on language beyond painting. That’s all I ever want to do in life, write poetry. To be a poet, ignorant and naive.

Streetview of Michael Rikio Ming Hee Ho’s studio in Harajuku at night. Courtesy of Amadour.